Shrinking Uncertainty

In the previous two posts we’ve explored:

- how credible predictions give you two estimates: the expected outcome and how much the realized/observed outcome could reasonably differ from that.

- how distributions can help us understand both expected value and the uncertainty around it.

In this post we’ll unpack a bit more how uncertainty works, and why (as we noted in the second post) we measure/estimate uncertainty. Spoiler alert: it’s because we can do something about the things we measure.

In the first post we mentioned that a lot of general interest in prediction can come off as ignore the uncertainty part of the prediction, as if its dirt swept under a rug. Maybe the name ‘uncertainty’ evokes some primal instinct to fill the unknown with the known.

Here’s two rebuttals to that instinct to ignore uncertainty: 1) knowing what you don’t know keeps you humble and teachable and gives you guidance about where to grow. And 2) just because one might not be able to know something perfectly does not in any way equate with not knowing it well. The ‘unknown’ ≠ the ‘unknowable’.

Measuring to Minimize

So now consider why shrinking the range of uncertainty around your estimate is advantageous.

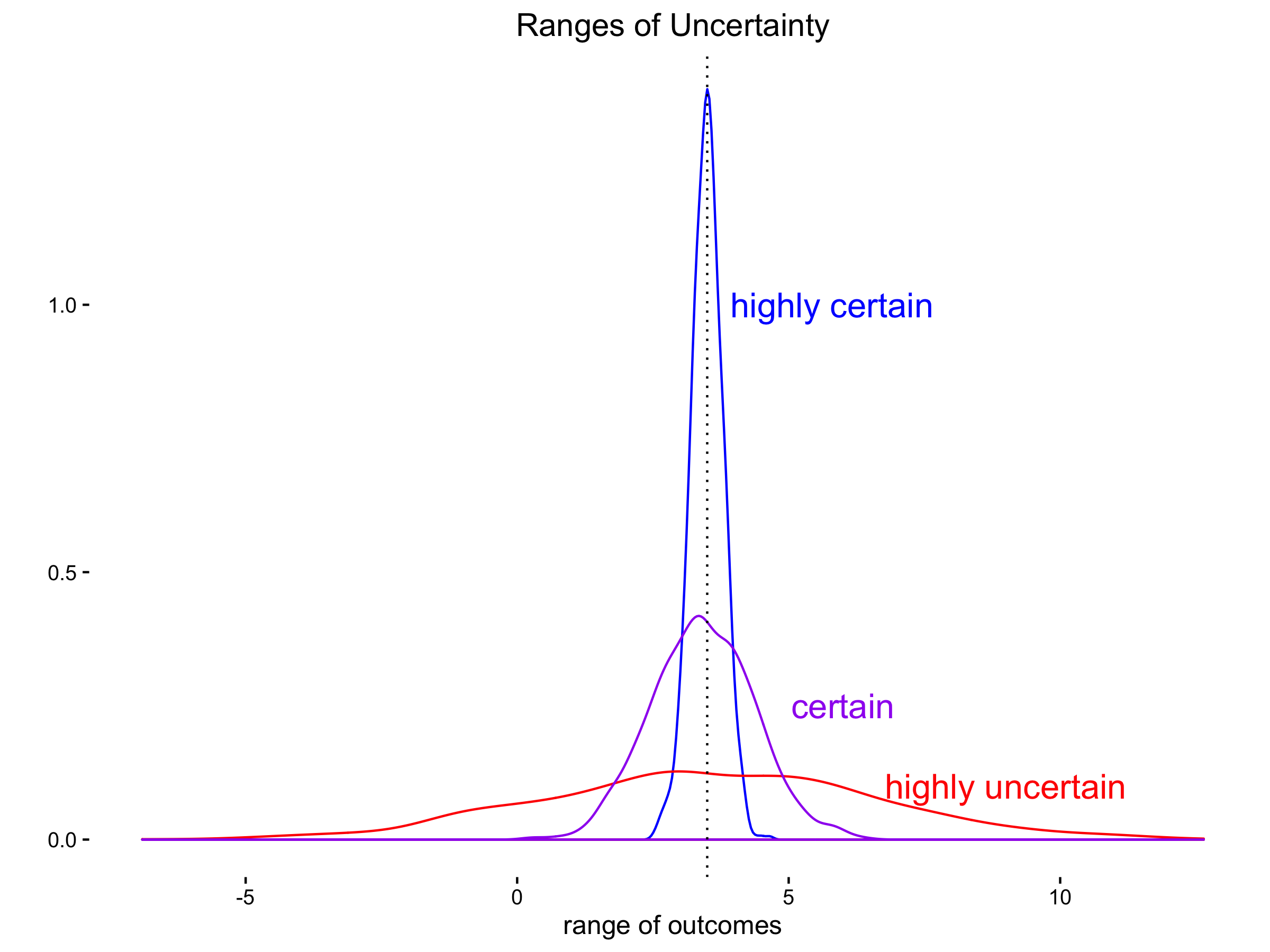

Working off of last post’s milk example, suppose a gallon of milk cost $1 one day and $15 the next. There is wide uncertainty ranges in the price of milk. In such a case, people under that pricing regime would suffer from not really knowing what to expect one day to the next. The market was totally unpredictable. When the uncertainty ranges are wide, the range of expected outcomes are wide around the expected outcome. And so when a given choice could result in either quite bad or quite good outcomes not a small percentage of the time, making a choice seems undesirable.

In such situations as this, people can only do conservative things and always save their money, never spend, never invest. This is why economies that are unstable are also stagnant. Noone knows enough about the future with enough confidence that they believe an investment or a purchase will have a positive return instead of loss.

When you can narrow the uncertainty ranges around an expected value to much tighter that means people believe their expectations are likely enough to act within an tolerable range in the actual outcomes. Thus, they can choose to take educated risks when the expectations seem favorable to them and also hedge when expectations seem foreboding.

Wrapping up

As I’ve described in earlier posts, we all do this type of prediction with uncertainty internally. So in statistical predictions, we should strive to incorporate both parts of the prediction.

Being precise doesn’t mean that uncertainty will go to zero; that would mean the outcome was so regular we wouldn’t even need predictions. Noone needs to predict gravity or the speed of light: they’re laws of natures and essentially constant.

So in situations where the outcomes are uncertain knowing any amount of what might happen is an improvement on not knowing anything at all. That reduces the uncertainty. And yet, precision in prediction will still want to estimate both the expected outcome and the uncertainty around that outcome: what we can expect and how that expectation may differ from what eventually happens.