Predictions and Everyday Distributions

Statisticians are often memed for giving “It depends” as an answer when people want solid stats. Statisticians aren’t wrong to say it depends, because the more you study something, the more you see how so many factors are at play that … well, it depends. But people aren’t wrong either for wanting actionable intell.

So is there a middle ground: is there a way to make “It depends” be more informative. We could ask, depends on what? This requires a lot more explaining from the statistician and often funds more research, but may still end in some sort of “It depends” answer. Another way to extract some insight from beyond “It depends” is ask over what range is depends, or to scope that range of possible outcomes with an answer to, how much does it depend?

And that’s where distributions come in. Distributions are one way to summarize and visualize “It depends”.

An Example

Suppose you have to drive to store to get milk.

To do this task, you must make a guess about how much it should cost before you actually see the price to decide how much money you’ll need to have in your wallet to buy it. You know you currently have $5 in your wallet. So you ask yourself: based on my past experience at the stores, is $5 enough to buy milk or do I need to go to the ATM first?

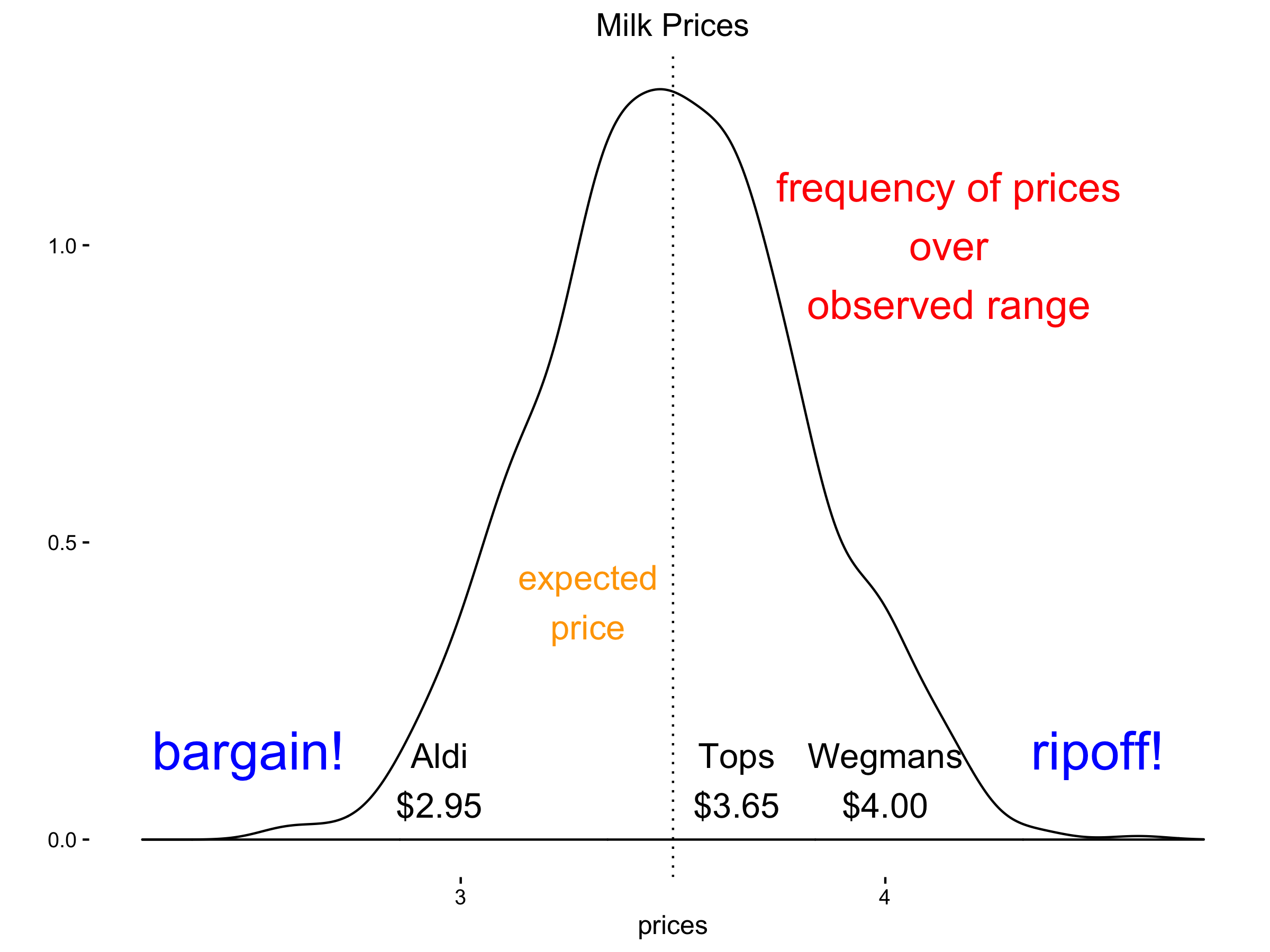

Let’s say from regularly shopping at different stores where you’ve seen prices as low as $2.75 and as high as $4.00 (this range makes up your confidence interval. You expect to see reasonable prices in this range.) you make a fairly educated guess: the average of all the prices I’ve seen in the past is around $3.50 and so you’d be pleasantly surprised to see it lower than 2.75 and angry to see it higher than 4.00. So you decide $5 is enough without going to the ATM.

When you get to Aldi, they have a sale on milk for $2.50. You are elated because this is much lower (significantly different on low side) than you expected the usual price would be, so you buy 2 cartoons. However, if you’d stopped at Wegman’s that day you would have been infuriated that the price was $4.50 because you thought it was a rip off (statistically different from the expected on the high side). Even though you had the money, you would have thought it was unfair and driven somewhere else.

That relates the usefulness of the price distribution above. It lets you put a range around your guess within which you will still follow through with your plan; any thing outside of that plan (on either side) requires a revision in some way. That distribution of price also measures your uncertainty of the actual price you’ll observe at any one place, but an assumption of what that range could reasonably be. If it goes beyond that reasonable scope, you have an interpretation ready for that and a likely action or attitude to that experience.